Tania León’s “Esencia” and Dvořák’s String Quartet Op. 61

5BMF’s 2021-2022 season closes on June 3 & 4, 2022, with two presentations of the Harlem Chamber Players in a program featuring iconic string quartets by Tania León and Antonin Dvořák. Dig into the music with our advance program notes below.

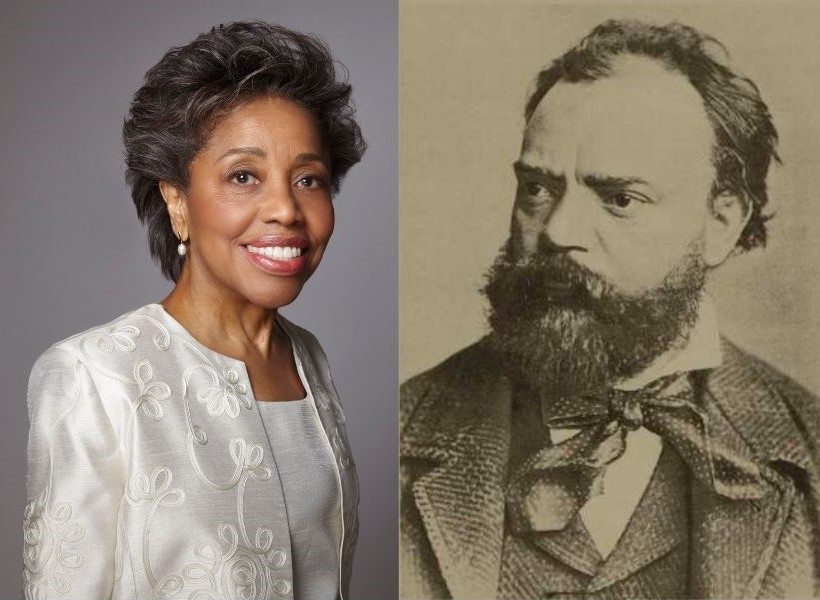

Despite the surface-level differences of their compositional styles, the similarities and connections between Tania León and Antonín Dvořák are surprising and important: the circuitous routes of their musical careers, their knack for synthesizing divergent musical influences, and their grounding in the traditional music of their homelands, Cuba and Bohemia (Čechy).

After years of rigorous musical training, León departed Cuba in 1967 at the age of 24 through a resettlement program, intent on traveling via the United States to Europe to begin a career as a touring concert pianist. Instead, shortly before boarding her flight, she learned that she wouldn’t be allowed to return to Cuba, nor could she leave the US, effectively trapping her in limbo. Following this shock, León found her way to New York City, to a scholarship to the New York College of Music which led, in turn, to her career’s first break: being recruited by the famed Arthur Mitchell as he was establishing the Dance Theater of Harlem. She would become its first music director in 1969, establishing its Music Department, Music School, and Orchestra.

Over the next ten years, León’s star steadily rose: she wrote her first compositions for the Dance Theater and additional commissions started to come in, and in 1978, she was recruited by Lukas Foss and the Brooklyn Philharmonic to establish a community concert series along with fellow composers Talib Hakim and Julius Eastman. A pivotal moment then came the following year, 1979, when León was finally able to travel back to Cuba, the first time she was able to be reunited with her family and homeland. The experience led to something of a lightbulb moment, inspiring León to combine her nascent compositional rigor with elements of the popular and folk musics she grew up hearing, a defining element of her style ever since.

León’s quartet Esencia, from 2009, finds these influences still very much at play, as she writes in her notes on the piece:

Esencia para cuarteto de cuerdas, reflects influences of classical genres of music in the Caribbean and Latino America. The word esencia, in English, is the essence or initial point that determines the behavior and the styles and an ensemble of needed characteristics for something to become what it is. The more obvious traces of these influences is in the myriad of syncopated gestures indigenous of: son, danzon, guajiras, montunos or echoes of a melodic line in the “Aguas de Rosas” movement. A melody that hearkens the sound of the quena, the traditional flute of the Andes. At times there is a crossover of Copland-esque harmonic overtones, influences of American culture, traces of a syncretic tendency in the musical language that depicts “here and now” while I composed the piece. A sort of commentary where the “esencia” of the piece merges, the same way that my personal musical language has syncretized my cultural experiences.

León’s music can be challenging, for the technical demands it places on its performers and the abstraction it presents to its audiences. As audience members, our expectation of instrumental music is so often that it depicts a narrative arc, as does Dvorak’s quartet on this program. Here, it is best to set aside that expectation in favor of something closer to a portrait or a portrayal of a state of being. From this stance, Esencia becomes quite affecting, a depiction, perhaps, of León’s creative process, of the ways in which fragments float through her consciousness as she’s writing, or at a higher level, the fragments and memories that make up all of our lives and essences.

For more reading about Tania León we recommend:

- Her official website

- William Robin’s engrossing profile in the New York Times

- Alejandro L. Madrid’s new biography Tania León’s Stride.

Antonín Dvořák’s String Quartet No. 11, Op. 61 comes out of his first big break as a composer in 1879 at age 37. Up until then, it could be said that Dvořák was a gigging musician who composed a little on the side in his spare time, spare time that led him to write at least ten string quartets, five symphonies, and an opera, among many other works. All of this music was essentially composed in secret, from 1866–1873, then gradually performed in Prague, but little elsewhere.

His working life in the early years of his musical career consisted mostly of private piano teaching and a position, starting in 1859, as the principal violist of the dance band of Karel Komzák, which played mostly in restaurants and at balls. The orchestra received a boost in 1862 when it became the house orchestra of the Provisional Theater, the first Czech theater in Prague, and again in 1867, when Bedřich Smetana, who would become an early champion of Dvořák’s music, became its conductor.

Dvořák’s sudden leap to fame came about, improbably, through what was essentially a government arts council grant application. At this time Bohemia was a part of the Cisleithania region of Austria-Hungary, with its emperor-king based in Vienna. As his composing activities began to gain momentum, Dvorak would send an annual application for funds to the Austrian State Stipendium, typically including scores to over a dozen compositions. After an initial rejection in 1873, he received his first award the next year, and in 1875, none other than Johannes Brahms joined the Stipendium’s panel. After three years of assessing Dvořák’s scores, in 1878 Brahms took it upon himself to write to his publisher Simrock:

“As for the state stipendium, for several years I have enjoyed works sent in by Antonín Dvořák (pronounced Dvorschak) of Prague. This year he has sent works including a volume of 10 duets for two sopranos and piano, which seem to me very pretty, and a practical proposition for publishing. […] Play them through and you will like them as much as I do. As a publisher, you will be particularly pleased with their piquancy. […] Dvořák has written all manner of things: operas (Czech), symphonies, quartets, piano pieces. In any case, he is a very talented man. Moreover, he is poor! I ask you to think about it!”

Simrock agreed to publish Dvořák’s music and within a year his works were being played widely, throughout Europe and as far away as Baltimore. His first major commissions also materialized, all from Vienna: for his Sixth Symphony, a violin concerto to be premiered by Joseph Joachim, and the string quartet on today’s program, what would become his Op. 61.

Within this context the quartet toes a fascinating line, clearly proceeding from Dvořák’s Czech-influenced voice, but with nods to some of the Viennese greats: an opening gesture and movement reminiscent of Schubert’s Cello Quintet; a wistful, dense, and slightly curious slow movement with shades of late Beethoven; and a last movement whose second theme cheekily hints at the opening of Brahms’ G Major Sextet. The Scherzo, however, with its playful alternation between divisions of 3 and 2, is clearly Czech in influence, its rhythmic play based on the Furiant folk dance, and the quartet as a whole feels unequivocally in Dvořák’s personal voice, its grandeur and drama evoking something of an epic folk tale.

The tension between Bohemian and Viennese influences in Dvořák’s writing would soon be mirrored in the public sphere, with a flare up of regional tensions leading many of Dvořák’s works to being struck from Viennese concert programs for a period of several years, even as his fame continued to grow outside the empire. In 1884 he wrote: “Viennese audiences seem to be prejudiced against a composition with a Slav flavor. [My Slavonic Rhapsody] went very well in London and Berlin, and will do well elsewhere too, but in the national and political conditions prevailing here I am afraid it will not be well received.”

When his publisher, Simrock, insisted on printing his name as the German “Anton,” Dvořák wrote: “an artist too has a fatherland in which he must also have a firm faith and which he must love.” Whether the tension of current events was the source of the dramatic tone of his quartet is up for debate, but it is a poignant picture to hear it within the context of this time when Dvořák was seemingly trapped between worlds and unsure of what the future would bring.